Relationship between continental chemical weathering trends in the North China Basin and the high-latitude glacial cycles from the Late Carboniferous to the Early Permian

-

摘要:目的和方法

晚古生代冰室期(LPIA;ca. 360~254 Ma)是地质历史时期唯一有记录冰室向温室过渡的时期,可以为冰川−环境−气候的协同演化和未来气候变化提供深时视角。为了深入理解晚石炭世—早二叠世低纬度地区大陆化学风化趋势和高纬度冈瓦纳地区冰川旋回之间的潜在联系,以华北盆地柳江煤田本溪组−太原组的泥岩为研究对象,利用由泥岩的元素地球化学数据计算得到的多种化学风化指标(CIA、CIW和PIA),重建柳江煤田的大陆化学风化趋势和古气候演变特征。

结果结果显示,低纬度柳江煤田的大陆化学风化作用的周期性变化,包括巴什基尔阶早−中期、莫斯科阶−卡西莫夫阶、阿瑟尔阶早期的3个风化减弱阶段和巴什基尔阶晚期、格舍尔阶的2个风化增强阶段。这种风化趋势的循环交替与高纬度冈瓦纳大陆的冰川旋回密切相关:风化趋势的减弱阶段代表了气候条件向相对凉爽干燥转变,这几乎与高纬度冰期同步,而风化趋势的增强阶段则代表了气候条件向相对温暖湿润的变化,这与高纬度间冰期同步。对比分析发现,间冰期内火山活动频发、大气CO2浓度升高、气候变暖、水文循环增强、海平面上升,共同促进了热带雨林面积缩减和大陆化学风化作用增强,为铝土矿的发育创造了有利条件;而冰期内火山活动减弱、气候变凉、CO2浓度减少、雨林面积扩张,导致大陆风化作用减弱,有利于煤和富有机质泥岩形成。

结论研究结果揭示了低纬度华北盆地大陆化学风化趋势与高纬度冈瓦纳冰川旋回和沉积矿产(如煤、铝土矿)分布之间的联系,为理解地质历史时期冰川−环境−气候的复杂相互作用机制提供了新视角。

Abstract:Objective and MethodsThe Late Paleozoic Ice Age (LPIA; ca. 360‒254 Ma), the only period recording the transition from icehouse to greenhouse conditions throughout the geological history, can provide a deep-time perspective for glacier-environment-climate coevolution and future climate change. To gain a deep understanding of the potential relationship between the continental chemical weathering trends in low-latitude regions and the glacial cycles in the high-latitude Gondwana region from the Late Carboniferous to the Early Permian, this study investigated the mudstones of the Benxi-Taiyuan formations, Liujiang coalfield, North China Basin. Using multiple chemical weathering indices such as chemical index of alteration (CIA), chemical index of weathering (CIW), and plagioclase index of alteration (PIA) calculated from the elemental geochemical data of the mudstones, this study reconstructed the continental chemical weathering trends and paleoclimatic evolutionary characteristics of the Liujiang coalfield.

ResultsThe results indicate that the periodic changes of continental chemical weathering in the low-latitude Liujiang coalfield involved three weathering weakening stages (i.e., early-middle Bashkirian, Moscovian-Kasimovian, and early Asselian) and two weathering enhancement stages (i.e., late Bashkirian and Gzhelian). This cyclic alternation of weathering trends was closely associated with the glacial cycles of the high-latitude Gondwanaland. The weathering weakening stages represent shifts to relatively cool and dry climates, roughly synchronous with the glacial periods at high latitudes. In contrast, the weathering enhancement stages suggest changes to relatively warm and humid climates, coinciding with the interglacial periods at high latitudes. The comparative analysis reveals that frequent volcanic activity, increased atmospheric CO2 concentration, climate warming, enhanced hydrologic cycles, and sea-level rise during the interglacial periods jointly contributed to the reduced area of tropical rainforests and the enhanced continental chemical weathering, creating favorable conditions for the formation of bauxite. In contrast, the weakening volcanic activity, cooling climate, reduced atmospheric CO2 concentration, and increased rainforest area during the glacial periods led to weakened continental weathering, facilitating the formation of coals and organic-rich mudstones.

ConclusionsThe results of this study reveal the relationship between the continental chemical weathering trends in the low-latitude North China Basin and the glacial cycles and the distributions of sedimentary minerals (e.g., coals and bauxite) in the high-latitude Gondwana region, providing a novel perspective for understanding the mechanisms underlying complex glacier-environment-climate interactions throughout the geological history.

-

晚古生代冰室期(LPIA;ca. 360~254 Ma),作为地质历史时期持续时间最长的冰川活动阶段,并非由单一的连续冰川事件构成,而是由一系列较短的离散冰期和间冰期组成 [1-4]。这些冰川旋回紧密伴随着高纬度冈瓦纳大陆冰盖的周期性扩张与消融[1-2],并标志着自维管植物登陆以来全球环境气候唯一一次从大规模冰室向温室的显著转变[5]。因此,开展该时期的研究不仅是认识地球过去的气候和环境变化及其控制机制(大陆风化−冰川−大气CO2−火山活动)的宝贵视角,也是预测未来气候变化趋势的重要窗口。

近年来,通过综合运用地层学、沉积学、古植物学、岩石学、地球化学及同位素地球化学等多学科方法,学者们对这一时期的气候演变进行了详细的研究[5-7],揭示了丰富的环境信息,但关于冰期−间冰期交替与火山活动、化学风化、构造运动等地质过程的内在联系,仍存诸多争议[8-10]。特别是岩石风化作用在陆地生态系统中扮演着至关重要的角色,它可以通过硅酸盐岩化学风化与大气CO2浓度的负反馈机制对长时间尺度的全球气候调控产生深远影响[11-12]。此外,鉴于岩石风化在地质碳汇中的核心地位,探讨其影响因素显得尤为重要。在全球尺度上,太阳活动、全球气候变化、大陆构型变迁、山系隆升、植被演化及风化产物的迁移与埋藏等因素,共同塑造了化学风化的宏观格局[13]。而在区域尺度上,区域构造特征、岩石类型、地理位置、气候条件、植被覆盖情况及地形地貌等,则成为影响化学风化过程的关键因素。因此,深入理解晚古生代冰室期岩石风化作用及其与气候演变的相互作用机制,对于揭示地质历史时期冰川−环境−气候的复杂关系,以及预测未来气候变化趋势,具有重要意义。

笔者以华北盆地柳江煤田本溪组−太原组下段作为研究对象,在已建立的年代地层框架基础上,利用多种化学风化指标,重建了柳江煤田的大陆风化趋势和气候演变特征。将这些数据和来源于同一地区的其他数据结合,深入探讨大陆风化作用、大气CO2浓度、火山活动等因素与气候变化的协同作用机制,为理解晚古生代冰室期气候变迁的多因素协变模式提供了新视角。

1 地质背景

在晚石炭世−早二叠世早期,华北盆地位于古特提斯洋东北缘[14],古纬度为20°~30°N,属于低纬度赤道地区[15] (图1a)。华北盆地南起秦岭造山带(伏牛古陆)、北至内蒙古隆起(阴山古陆),西起贺兰山、东至郯庐断裂及其东侧的胶东、辽东和朝鲜半岛的南端[16] (图1b)。受加里东运动的影响,华北盆地内石炭−二叠纪地层平行不整合覆盖在奥陶纪碳酸盐岩之上,连续沉积了本溪组、太原组和山西组这套主要含煤地层,其中自下而上分别发育了6层煤(6—1号)和铝土矿(G—B层)[16] (图1c)。在该时期内,沉积物源主要来自于华北盆地北部内蒙古隆起(阴山古陆),岩性为高度变质的太古宙和古元古代岩石[17]。

柳江煤田面积大约 300 km2,位于华北盆地的东北部,总体上为一向斜构造,轴向近南北向,东翼地层倾角较缓,西翼地层较陡,局部还存在地层倒转结构[22]。在本研究中,目标地层为柳江煤田石门寨剖面晚石炭世—早二叠世早期的本溪组−太原组下段。其中本溪组厚度约80 m,下部为紫色铁质泥岩(风化壳)和铝土矿(G层)、炭质页岩和粉砂岩,含薄煤层(6号);上部为中−细粒石英砂岩、粉砂岩与页岩互层,顶部灰质泥岩夹泥灰岩透镜体,与下伏的中奥陶统马家沟组灰岩呈不整合接触(图1c)。太原组厚51 m,底部为灰黄色球状风化的中、细粒砂岩;下部为页岩、夹薄煤层(5号)和铝土矿(D层);上部为灰黑色炭质页岩、粉砂质泥岩,夹煤层(4号,3号),与下伏的本溪组呈整合接触(图1c)。研究区本溪组和太原组主要为海陆过渡相沉积环境,自晚石炭世以来,华北盆地开始缓慢沉降,此时研究区属于沿海低地,发生间歇性的海侵事件,沉积了一套海陆过渡相的含煤地层;至晚石炭世末期地壳缓慢抬升,海平面下降,到早二叠世研究区逐渐过渡为陆相沉积,形成了河、湖、沼泽相沉积[23-24]。根据锆石U-Pb定年数据、植物和孢粉化石的组成,将研究地层约束为晚石炭世巴什基尔早期—早二叠世阿瑟尔早期(图1c)[18-19]。

2 材料与方法

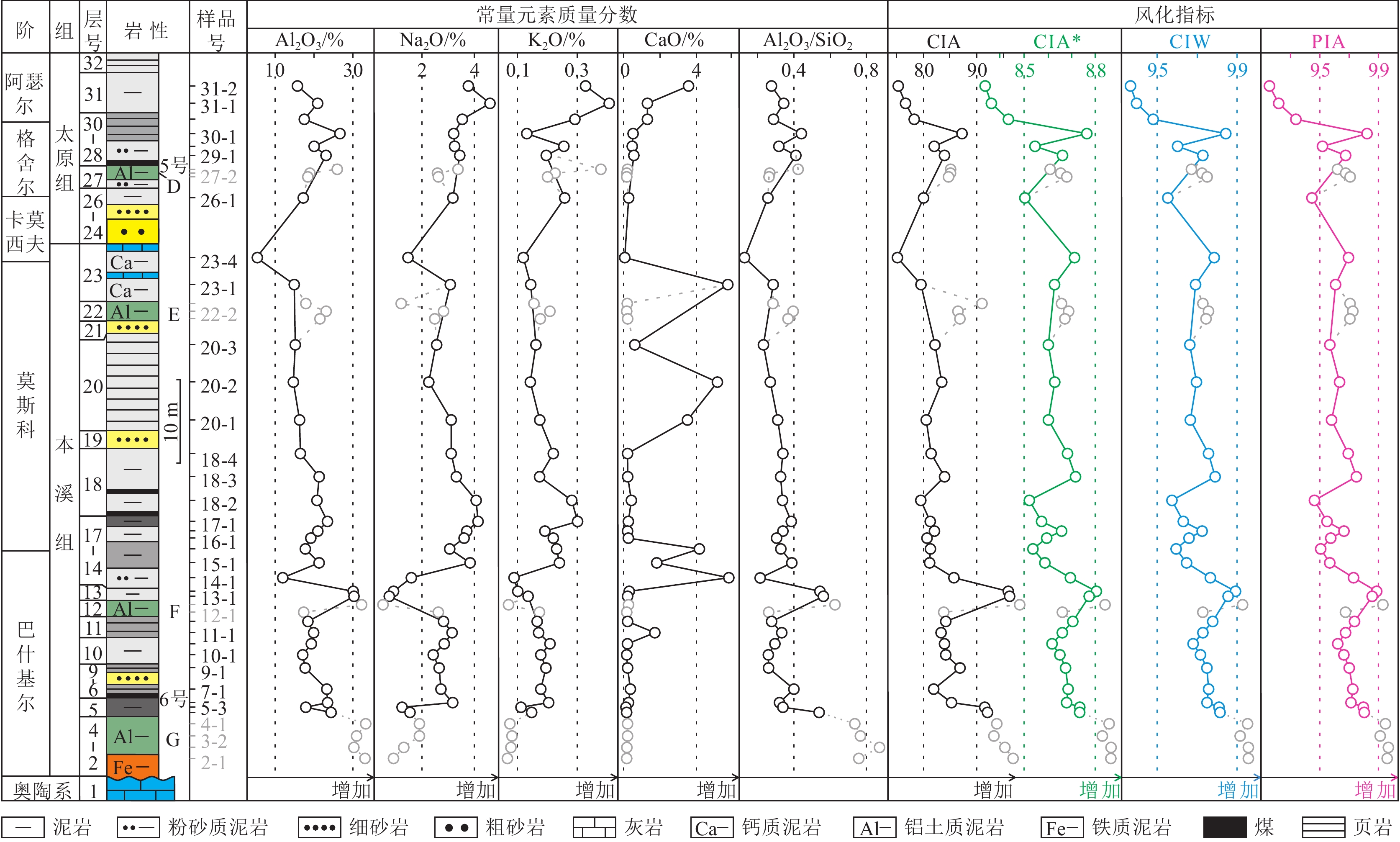

在华北盆地东北缘的石门寨剖面(40.1°N,119.6°E),采集了本溪组34件、太原组10件,共44件新鲜泥岩样品。其中包括1件紫红色铁质泥岩(风化壳)和11件灰白色铝土质泥岩样品(G—D层),采样位置如图2所示。将采集的新鲜泥岩样品破碎至200目(0.74 mm)后进行常微量元素测试。

常微量元素测试在核工业北京地质研究院开展,常量元素测试依照GB/T 14506.14—2010《硅酸盐岩石化学分析方法第14部分:氧化亚铁量测定》和GB/T 14506.28—2010《硅酸盐岩石化学分析方法第28部分:16个主次成分量测定》,采用熔片X射线荧光光谱法(XRF),利用型号为 PW2404的荧光光谱仪进行,分析误差为±5%;微量元素测试根据GB/T 14506.30—2010《硅酸盐岩石化学分析方法第30部分:44个元素量测定》,使用封闭酸溶—电感耦合等离子体质谱仪(ICP—MS)进行测定,分析误差小于10%。

化学蚀变指数(CIA)、化学风化指数(CIW)和斜长石蚀变指数(PIA)作为反映源区化学风化作用的强度指标之一[25-27],被广泛用于重建不同地质时期的大陆化学风化趋势。CIA由H. W. Nesbitt等[25]首次提出,主要用来判断物源区的风化程度。下文用化学式表示其量符号。

$$ \mathrm{C}\mathrm{I}\mathrm{A}=\frac{{\mathrm{A}\mathrm{l}}_{2}{\mathrm{O}}_{3}}{{\mathrm{A}\mathrm{l}}_{2}{\mathrm{O}}_{3}+{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{O}}^{\mathrm{*}}+{\mathrm{N}\mathrm{a}}_{2}\mathrm{O}+{\mathrm{K}}_{2}\mathrm{O}}\times 100 $$ (1) 由于成岩作用过程中钾交代作用会带入新的钾元素,从而导致CIA计算值偏低。因此,L. Harnois [28]提出了化学风化指数(CIW),从CIA计算公式中排除了K2O的含量:

$$ \mathrm{C}\mathrm{I}\mathrm{W}=\frac{{\mathrm{A}\mathrm{l}}_{2}{\mathrm{O}}_{3}}{{\mathrm{A}\mathrm{l}}_{2}{\mathrm{O}}_{3}+{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{O}}^{\mathrm{*}}+{\mathrm{N}\mathrm{a}}_{2}\mathrm{O}}\times 100 $$ (2) C. M. Fedo等[24]提出斜长石蚀变指数(PIA),用于判断斜长石的风化程度:

$$ \mathrm{P}\mathrm{I}\mathrm{A}=\frac{{\mathrm{A}\mathrm{l}}_{2}{\mathrm{O}}_{3}-{\mathrm{K}}_{2}\mathrm{O}}{{\mathrm{A}\mathrm{l}}_{2}{\mathrm{O}}_{3}+{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{O}}^{\mathrm{*}}+{\mathrm{N}\mathrm{a}}_{2}\mathrm{O}-{\mathrm{K}}_{2}\mathrm{O}}\times 100 $$ (3) 式(1)—式(3)中,氧化物单位均为摩尔数,其中CaO*指硅酸盐矿物中所含的CaO。为排除非硅酸盐矿物中的CaO,CaO*的计算和矫正过程遵循S. M. McLennan(1993)提出的方法[29]。

3 结果与分析

若泥质岩在源区以外的区域经历了再旋回作用(二次风化),这将导致CIA的计算结果偏大,从而无法反映物源区的真实风化强度[30]。在研究区,本溪组底部发育一套古风化壳,主要由铁铝质黏土岩和铝土岩组成,代表了强烈的风化作用和淋滤作用的产物。在其形成过程中,元素Ca、Na、K等大量流失,无法准确显示物源区的特征。因此,本文计算化学风化指数时,将研究区地层中的风化壳和铝土矿层排除在外(图2)。

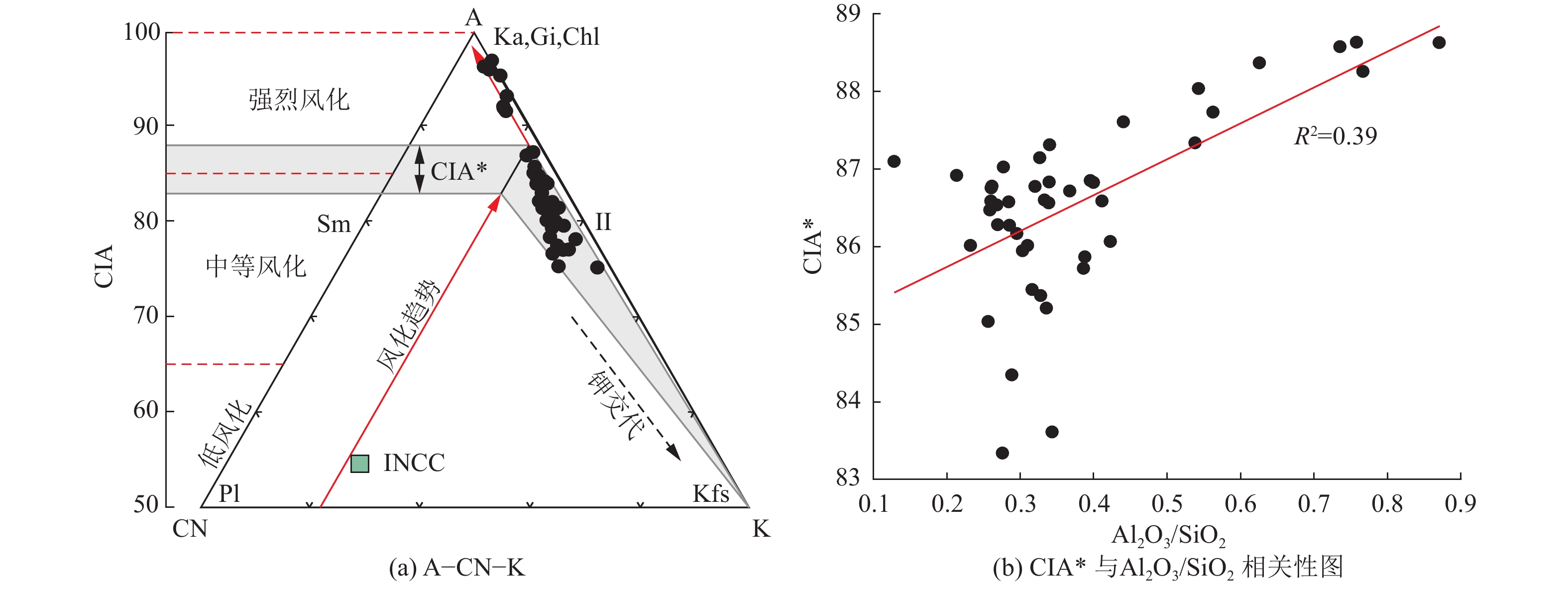

如图3a所示,将研究区泥岩样品数据投到A-CN-K 图中,可以发现大部分样品均偏离理想风化趋势线,这表明钾交代作用对泥质岩样品产生一定的影响[26]。在A-CN-K图解中,通过K2O端元与样品点连线的反向延伸线与未发生钾交代作用风化趋势线的交点,即代表钾交代作用之前的CIA 值(图3a)[26]。另外,也可利用A.Panahi 等[31]提出的K2O的校正公式,使用校正后的 K2Ocorr值重新计算便可得到矫正过的CIA*值。

![]() 图 3 石门寨剖面晚石炭世—早二叠世早期大陆风化趋势和泥岩的CIA*与Al2O3/SiO2之间的相关性分析A=Al2O3;CN=CaO* + Na2O;K=K2O;Ka—高岭石;Gi—三水铝石;Chl—绿泥石;Sm—蒙脱石;Il—伊利石;Pl—斜长石;Kfs—钾长石;CIA*为钾交代校正过后的化学蚀变指数;INCC为华北克拉通内部Figure 3. Continental weathering trends and the correlation between CIA* and Al2O3/SiO2 ratio of mudstones in the Benxi-Taiyuan formations for the Shimenzhai section from Late Carboniferous to the Early Permian

图 3 石门寨剖面晚石炭世—早二叠世早期大陆风化趋势和泥岩的CIA*与Al2O3/SiO2之间的相关性分析A=Al2O3;CN=CaO* + Na2O;K=K2O;Ka—高岭石;Gi—三水铝石;Chl—绿泥石;Sm—蒙脱石;Il—伊利石;Pl—斜长石;Kfs—钾长石;CIA*为钾交代校正过后的化学蚀变指数;INCC为华北克拉通内部Figure 3. Continental weathering trends and the correlation between CIA* and Al2O3/SiO2 ratio of mudstones in the Benxi-Taiyuan formations for the Shimenzhai section from Late Carboniferous to the Early Permian在研究区,CIA*值(校正后的CIA值)为83.34~88.04,平均86.26(图2,附表1)。根据CIA*在垂向上的变化趋势,可以识别出2个高值区和3个低值区(图2)。其中2个高值区的值分别为88.04~87.73(平均87.89)和87.61~85.45(平均86.55),并对应于巴什基尔阶晚期和格舍尔阶;3个低值区的值分别为87.34~86.17(平均86.81)、87.15~85.04(平均86.15)和84.35~83.34(平均83.77),并对应于巴什基尔阶早期和中期、莫斯科阶至卡西莫夫阶、阿瑟尔阶(图2)。

1 石门寨剖面常微量元素和大陆风化指标1. Normal and trace elements and continental weathering trends in Shimenzhai sections样品编号 常量元素质量分数/% Al2O3/SiO2 Th/U CIA CIA* CIW PIA Al2O3 CaO K2O Na2O Sm31-2 15.66 3.52 3.77 0.32 0.28 3.5 75.24 83.34 93.64 91.58 Sm31-1 20.99 1.29 4.66 0.41 0.34 3.4 76.61 83.61 93.95 92.18 Sm30-2 17.42 1.28 3.56 0.29 0.29 3.5 78.31 84.35 94.77 93.38 Sm30-1 26.70 0.49 3.22 0.13 0.44 3.2 87.20 87.61 98.44 98.20 Sm29-2 20.02 0.45 3.26 0.25 0.32 2.4 82.08 85.45 96.01 95.19 Sm29-1 23.04 0.54 3.46 0.20 0.41 3.4 83.98 86.59 97.29 96.78 Sm27-4 25.95 0.19 3.37 0.37 0.42 3.8 85.11 86.07 96.71 96.19 Sm27-3 18.91 0.13 2.57 0.22 0.27 4.2 85.04 86.54 97.23 96.77 Sm27-2 18.41 0.14 2.63 0.20 0.26 3.7 84.70 86.78 97.50 97.06 Sm26-1 17.11 0.26 3.19 0.26 0.26 4.3 80.07 85.04 95.55 94.48 Sm23-4 5.08 0.08 1.45 0.12 0.13 3.5 75.10 87.10 97.86 96.93 Sm23-1 14.81 5.95 3.09 0.14 0.29 5.4 79.49 86.28 96.94 96.08 Sm22-3 17.86 0.22 1.18 0.15 0.28 2.5 90.93 86.58 97.28 97.07 Sm22-2 23.10 0.16 2.82 0.21 0.40 4.0 86.42 86.85 97.59 97.23 Sm22-1 21.52 0.19 2.48 0.18 0.37 3.0 86.85 86.72 97.43 97.08 Sm20-3 15.19 0.62 2.55 0.16 0.23 2.6 82.18 86.02 96.65 95.93 Sm20-2 14.64 5.14 2.26 0.14 0.27 3.8 83.40 86.29 96.95 96.36 Sm20-1 16.30 3.46 3.12 0.17 0.31 2.3 80.49 86.01 96.64 95.80 Sm18-4 16.49 0.20 3.10 0.22 0.34 3.6 81.37 86.83 97.56 96.96 Sm18-3 21.18 0.18 3.32 0.17 0.33 1.9 83.94 87.15 97.92 97.50 Sm18-2 20.70 0.42 4.06 0.28 0.34 2.1 79.53 85.21 95.74 94.65 Sm17-1 23.47 0.27 4.15 0.30 0.39 4.7 81.29 85.72 96.32 95.48 Sm16-2 20.95 0.21 3.70 0.19 0.34 4.7 81.98 86.57 97.27 96.64 Sm16-1 19.09 0.23 3.61 0.22 0.30 4.0 80.60 85.95 96.58 95.73 Sm15-2 17.72 4.14 3.05 0.23 0.33 3.3 81.35 85.37 95.92 95.03 Sm15-1 21.28 1.77 3.83 0.24 0.39 4.2 81.18 85.87 96.48 95.66 Sm14-1 11.96 6.15 1.58 0.09 0.21 3.5 85.67 86.92 97.66 97.28 Sm13-2 30.12 0.28 0.89 0.10 0.54 6.6 95.88 88.04 98.92 98.88 Sm13-1 30.33 0.23 0.72 0.13 0.56 6.4 96.13 87.73 98.58 98.54 Sm12-2 32.23 0.24 0.38 0.07 0.63 4.1 98.03 88.37 99.29 99.28 Sm12-1 17.25 0.16 2.62 0.17 0.26 3.6 83.84 86.59 97.29 96.77 Sm11-2 18.40 0.22 2.81 0.16 0.28 4.0 84.15 87.03 97.78 97.35 Sm11-1 19.83 1.71 3.16 0.17 0.33 4.6 83.29 86.60 97.30 96.76 Sm10-2 19.36 0.21 2.84 0.21 0.30 4.6 83.89 86.17 96.82 96.24 Sm10-1 16.89 0.17 2.42 0.17 0.26 3.2 84.13 86.47 97.16 96.66 Sm9-1 17.66 0.20 2.65 0.19 0.26 3.9 86.85 86.76 97.48 97.00 Sm7-1 23.27 0.35 2.71 0.18 0.40 2.6 81.92 86.83 97.56 97.22 Sm5-3 23.46 0.24 3.17 0.20 0.32 3.6 85.31 86.78 97.50 97.09 Sm5-2 17.87 0.12 1.22 0.11 0.34 1.0 91.46 87.32 98.11 97.96 Sm5-1 24.41 0.16 1.54 0.15 0.54 1.6 91.96 87.34 98.13 98.00 Sm4-1 33.30 0.18 1.90 0.07 0.74 5.9 93.75 88.58 99.52 99.49 Sm3-2 30.96 0.20 1.88 0.08 0.77 6.6 93.08 88.26 99.17 99.11 Sm3-1 30.34 0.16 1.29 0.08 0.87 6.4 95.21 88.63 99.58 99.56 Sm2-1 33.13 0.17 0.91 0.06 0.76 6.9 96.72 88.63 99.59 99.57 此外,CIW 和 PIA的数据曲线与 CIA*数据相似(图2,附表1),在垂向上这三者也呈现了相同的变化趋势,证明了矫正后CIA*数据的有效性[32]。在巴什基尔阶早−中期内,CIW和PIA的变化范围分别为98.13~96.82和98~96.24(平均97.54和97.14);到巴什基尔阶晚期CIW和PIA值升高,分别为98.92~98.58和98.88~98.54(平均98.57和98.71);在莫斯科阶—卡西莫夫阶内CIW和PIA值有所降低,分别为97.92~95.55和97.5~94.48(平均96.8和96.04);之后到格舍尔阶CIW和PIA值重新升高,分别为98.44~96.01和98.2~95.19(平均97.24和96.73);最后在阿瑟尔阶内CIW和PIA值快速降低,变化范围分别为94.77~93.64和93.38~91.58(平均94.12和92.38)。

由于化学风化指数易被其他因素所影响,如物源区的母岩成分和性质、沉积过程中的水力分选作用、沉积再旋回作用和成岩作用[27]。可利用Al2O3/SiO2[33]、Th/U[34]和可以判断泥岩的CIA值是否受到沉积过程中的水力分选作用、沉积循环作用。在研究区,Th/U为1.0~6.9,平均3.8,可以排除母岩再循环作用的影响(附表1)。这是由于U4+被氧化为U6+并作为可溶组分被去除,导致了再旋回泥岩沉积物的 Th/U 比通常大于 6[34]。而Al2O3/SiO2是水力分选的化学指标,反映了泥浆中黏土矿物的浓度,以及沙子中石英和长石的浓度[33]。所示,它们之间存在较差的相关性(R2=0.39),这表示研究地层中的化学风化指标不受水力分选的影响[33]。综上,认为柳江煤田CIA*值是反映大陆风化趋势及其对应的古气候变化的可靠指标。

4 讨 论

大陆风化作用是一个复杂的过程,在约10万年(<0.1 Myr)的短时间尺度上,主要受温度和径流的影响,而大气CO2作为一种温室气体,其浓度的高低一定程度上可以用来表征大气温度的变化[23],因此,大气CO2浓度的升高对应着全球气温的升高,同时增强全球径流,引起大陆风化作用加剧。而长时间尺度上,约100万年(<1Myr)内主要受构造隆升的影响[35],构造隆升能导致更高和更陡峭的地形、加快物理侵蚀率与更多新鲜矿物的出露,从而增强大陆风化作用。其他因素如火山作用通常是通过释放CO2,影响大气CO2浓度从而间接影响化学风化。此外,土壤、物理侵蚀、植被覆盖等多种因素共同影响大陆化学风化[36-37]。

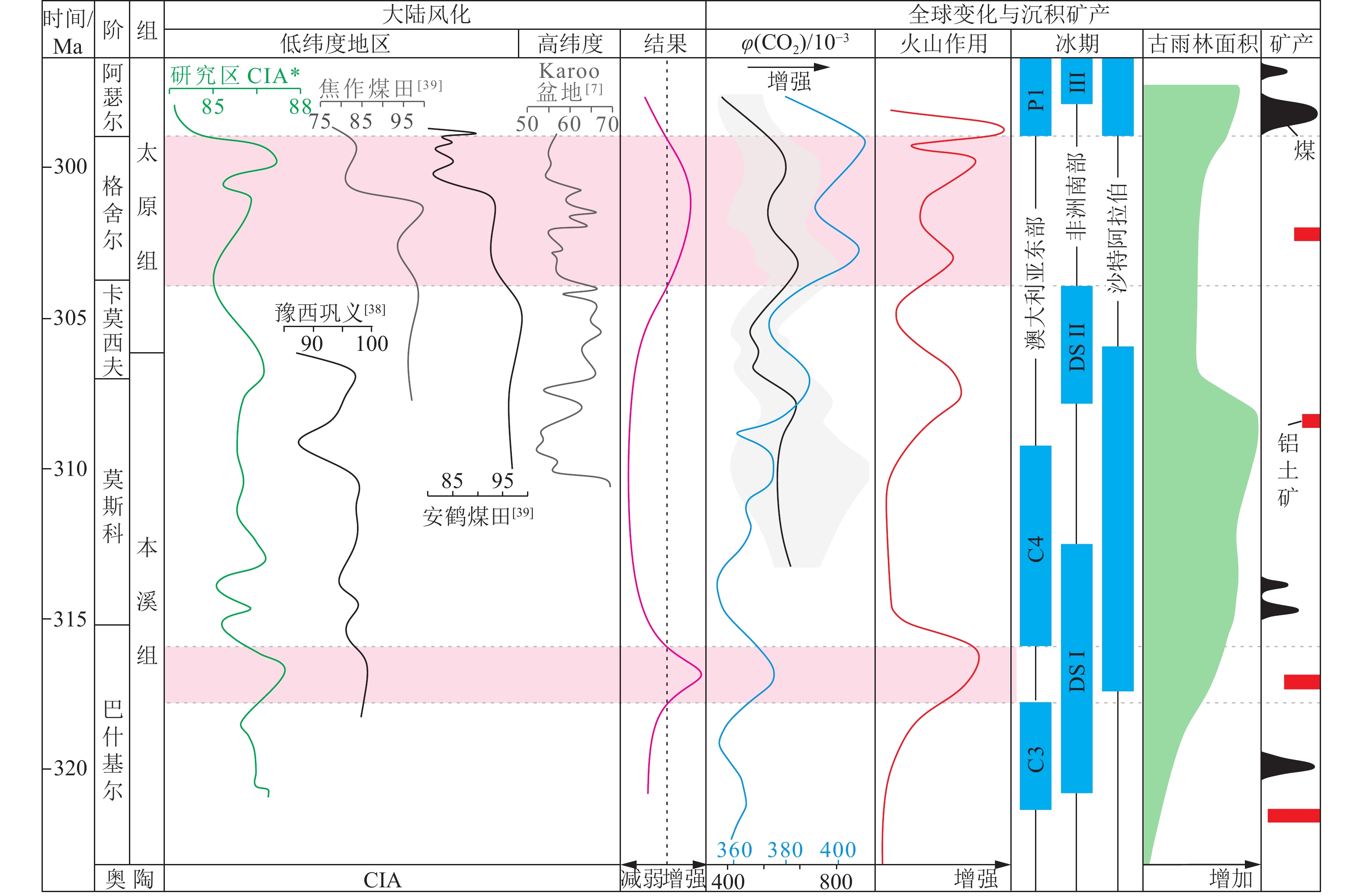

本次收集了低纬度地区华北盆地的柳江煤田、巩义地区[38]、焦作煤田[39]、安鹤煤田[37]和高纬度地区南非 Karoo 盆地[7,37]同时期的CIA曲线进行对比分析。发现它们具有相似的变化趋势(图4),但在数值的变化范围上华北盆地(CIA>70) 较Karoo盆地(CIA>50)普遍更高,表明在低纬度近赤道地区的化学风化作用更强,气候比高纬度地区更为温暖潮湿。如图4所示,把研究区CIA*曲线置于年代地层框架内分析得到,在巴什基尔阶早—中期内,研究区的大陆风化作用呈现下降趋势,低风化强度表明整个地区经历了向凉爽气候条件转变的过程。此时的低风化强度和凉爽气候条件与冈瓦纳高纬度地区存在的冰川(澳大利亚东部C3和南非Deglaciation Sequences I)相对应[2,20-21]。在巴什基尔阶晚期的大陆风化作用首次出现大幅度上升,表明研究区的气候条件向更温暖湿润变化,对应澳大利亚东部地区冰川期C3的结束和C4开始之间的间隔中,即间冰期[2]。随后在莫斯科阶—卡西莫夫阶内大陆风化作用再次下降,整体偏低,内部存在小幅度波动(图4),此时研究区由温暖潮湿转向凉爽干旱的气候条件,对应冈瓦纳高纬度地区冰川(澳大利亚东部C4、南非DS Ⅱ和阿拉伯)的启动和扩张[2,20-21]。这期间内出现的风化作用小幅度波动,可能与冈瓦纳高纬度不同地区冰川的扩张和消融有关[2,20-21,40]。至格舍尔阶,大陆风化作用再次上升(图4),研究区再次步入温暖潮湿的气候条件,这和冈瓦纳高纬度地区冰川(澳大利亚东部C4、南非DS Ⅱ和阿拉伯)的消融,开始进入间冰期相对应[2,21]。最后,在阿瑟尔阶大陆风化作用发生大幅度下降,风化强度达到最低,这对应冈瓦纳高纬度地区冰川(澳大利亚东部P1、南非DS Ⅲ和阿拉伯)的启动和扩张[2,21]。

综上,据研究区和同时期低纬度其他地区由多种化学风化指标得到的研究区大陆风化趋势,拟合出华北盆地晚石炭世—早二叠世早期大陆化学风化趋势结果,并发现其与高纬度冈瓦纳地区的冰川型沉积记录相联系发现具有良好的对应关系(图4)。

同时将巴什基尔阶至阿瑟尔阶早期内的华北盆地大陆化学风化趋势与全球同时期的冰川作用[1-2]、大气CO2浓度[41-42]、火山活动[18,43-45]、古雨林面积[46]等进行对比分析,发现华北地区大陆风化作用的增强与冈瓦纳高纬度地区冰川消融、大气CO2含量高、火山活动强、古雨林面积收缩等现象几乎同时发生(图4)。相反,华北地区大陆风化作用的减弱与冈瓦纳高纬度地区冰川扩张、大气CO2含量低、火山活动弱、古雨林面积扩张等现象具有一致性(图4)。这也表明低纬度地区矿产聚集特征与高纬度冈瓦纳地区冰川旋回有关[16,47],如冰期内寒冷的气候、较低的大气CO2浓度和海平面的下降,使得大陆化学风化受抑制,有利于有机质的产生和保存,即在冰期内煤和富有机质泥岩大量形成(图4);而间冰期温暖的气候、增强的水文循环和径流量,有利于大陆化学风化,进而促进了风化产物在排水良好的条件下经历再风化和淋滤作用,即在间冰期内铝土矿等沉积矿产大量形成(图4)。低纬度华北盆地的大陆化学风化趋势响应了高纬度冈瓦纳地区的冰川旋回,这一研究结果为深入理解该时期冰川−环境−气候的协同演化提供了新的视角。

5 结 论

(1) 在华北盆地晚石炭世—早二叠世早期本溪组—太原组下段,识别出大陆化学风化作用的2个高值区和3个低值区。其中,2个高值区(CIA*平均值87.89和86.55)分别对应于巴什基尔阶晚期、格舍尔阶,3个低值区(CIA*平均值为86.81、86.15和83.77),分别对应于巴什基尔阶早中期、莫斯科阶—卡西莫夫阶和阿瑟尔阶。

(2) 揭示了低纬度地区华北盆地晚石炭世—早二叠世泥岩记录的大陆化学风化趋势对高纬度冈瓦纳大陆冰川旋回(冰期−间冰期)的响应,即大陆风化趋势的上升和下降分别对应于冰川的消融(间冰期)和扩张(冰期)。研究成果对了解地球深时古气候−环境变化提供了一种新的视角,对预测未来气候变化具有一定的启示意义。

-

图 3 石门寨剖面晚石炭世—早二叠世早期大陆风化趋势和泥岩的CIA*与Al2O3/SiO2之间的相关性分析

A=Al2O3;CN=CaO* + Na2O;K=K2O;Ka—高岭石;Gi—三水铝石;Chl—绿泥石;Sm—蒙脱石;Il—伊利石;Pl—斜长石;Kfs—钾长石;CIA*为钾交代校正过后的化学蚀变指数;INCC为华北克拉通内部

Fig. 3 Continental weathering trends and the correlation between CIA* and Al2O3/SiO2 ratio of mudstones in the Benxi-Taiyuan formations for the Shimenzhai section from Late Carboniferous to the Early Permian

1 石门寨剖面常微量元素和大陆风化指标

1 Normal and trace elements and continental weathering trends in Shimenzhai sections

样品编号 常量元素质量分数/% Al2O3/SiO2 Th/U CIA CIA* CIW PIA Al2O3 CaO K2O Na2O Sm31-2 15.66 3.52 3.77 0.32 0.28 3.5 75.24 83.34 93.64 91.58 Sm31-1 20.99 1.29 4.66 0.41 0.34 3.4 76.61 83.61 93.95 92.18 Sm30-2 17.42 1.28 3.56 0.29 0.29 3.5 78.31 84.35 94.77 93.38 Sm30-1 26.70 0.49 3.22 0.13 0.44 3.2 87.20 87.61 98.44 98.20 Sm29-2 20.02 0.45 3.26 0.25 0.32 2.4 82.08 85.45 96.01 95.19 Sm29-1 23.04 0.54 3.46 0.20 0.41 3.4 83.98 86.59 97.29 96.78 Sm27-4 25.95 0.19 3.37 0.37 0.42 3.8 85.11 86.07 96.71 96.19 Sm27-3 18.91 0.13 2.57 0.22 0.27 4.2 85.04 86.54 97.23 96.77 Sm27-2 18.41 0.14 2.63 0.20 0.26 3.7 84.70 86.78 97.50 97.06 Sm26-1 17.11 0.26 3.19 0.26 0.26 4.3 80.07 85.04 95.55 94.48 Sm23-4 5.08 0.08 1.45 0.12 0.13 3.5 75.10 87.10 97.86 96.93 Sm23-1 14.81 5.95 3.09 0.14 0.29 5.4 79.49 86.28 96.94 96.08 Sm22-3 17.86 0.22 1.18 0.15 0.28 2.5 90.93 86.58 97.28 97.07 Sm22-2 23.10 0.16 2.82 0.21 0.40 4.0 86.42 86.85 97.59 97.23 Sm22-1 21.52 0.19 2.48 0.18 0.37 3.0 86.85 86.72 97.43 97.08 Sm20-3 15.19 0.62 2.55 0.16 0.23 2.6 82.18 86.02 96.65 95.93 Sm20-2 14.64 5.14 2.26 0.14 0.27 3.8 83.40 86.29 96.95 96.36 Sm20-1 16.30 3.46 3.12 0.17 0.31 2.3 80.49 86.01 96.64 95.80 Sm18-4 16.49 0.20 3.10 0.22 0.34 3.6 81.37 86.83 97.56 96.96 Sm18-3 21.18 0.18 3.32 0.17 0.33 1.9 83.94 87.15 97.92 97.50 Sm18-2 20.70 0.42 4.06 0.28 0.34 2.1 79.53 85.21 95.74 94.65 Sm17-1 23.47 0.27 4.15 0.30 0.39 4.7 81.29 85.72 96.32 95.48 Sm16-2 20.95 0.21 3.70 0.19 0.34 4.7 81.98 86.57 97.27 96.64 Sm16-1 19.09 0.23 3.61 0.22 0.30 4.0 80.60 85.95 96.58 95.73 Sm15-2 17.72 4.14 3.05 0.23 0.33 3.3 81.35 85.37 95.92 95.03 Sm15-1 21.28 1.77 3.83 0.24 0.39 4.2 81.18 85.87 96.48 95.66 Sm14-1 11.96 6.15 1.58 0.09 0.21 3.5 85.67 86.92 97.66 97.28 Sm13-2 30.12 0.28 0.89 0.10 0.54 6.6 95.88 88.04 98.92 98.88 Sm13-1 30.33 0.23 0.72 0.13 0.56 6.4 96.13 87.73 98.58 98.54 Sm12-2 32.23 0.24 0.38 0.07 0.63 4.1 98.03 88.37 99.29 99.28 Sm12-1 17.25 0.16 2.62 0.17 0.26 3.6 83.84 86.59 97.29 96.77 Sm11-2 18.40 0.22 2.81 0.16 0.28 4.0 84.15 87.03 97.78 97.35 Sm11-1 19.83 1.71 3.16 0.17 0.33 4.6 83.29 86.60 97.30 96.76 Sm10-2 19.36 0.21 2.84 0.21 0.30 4.6 83.89 86.17 96.82 96.24 Sm10-1 16.89 0.17 2.42 0.17 0.26 3.2 84.13 86.47 97.16 96.66 Sm9-1 17.66 0.20 2.65 0.19 0.26 3.9 86.85 86.76 97.48 97.00 Sm7-1 23.27 0.35 2.71 0.18 0.40 2.6 81.92 86.83 97.56 97.22 Sm5-3 23.46 0.24 3.17 0.20 0.32 3.6 85.31 86.78 97.50 97.09 Sm5-2 17.87 0.12 1.22 0.11 0.34 1.0 91.46 87.32 98.11 97.96 Sm5-1 24.41 0.16 1.54 0.15 0.54 1.6 91.96 87.34 98.13 98.00 Sm4-1 33.30 0.18 1.90 0.07 0.74 5.9 93.75 88.58 99.52 99.49 Sm3-2 30.96 0.20 1.88 0.08 0.77 6.6 93.08 88.26 99.17 99.11 Sm3-1 30.34 0.16 1.29 0.08 0.87 6.4 95.21 88.63 99.58 99.56 Sm2-1 33.13 0.17 0.91 0.06 0.76 6.9 96.72 88.63 99.59 99.57 -

[1] ISBELL J L,MILLER M F,WOLFE K L,et al. Timing of Late Paleozoic glaciation in Gondwana:Was glaciation responsible for the development of Northern Hemisphere cyclothems?[M]//Extreme depositional environments:Mega end members in geologic time. Boulder,Colorado:Geological Society of America,2003,370:5–24

[2] FIELDING C R,FRANK T D,BIRGENHEIER L P,et al. Stratigraphic imprint of the late palaeozoic ice age in eastern Australia:A record of alternating glacial and nonglacial climate regime[J]. Journal of the Geological Society,2008,165(1):129−140. DOI: 10.1144/0016-76492007-036

[3] HORTON D E,POULSEN C J,POLLARD D. Orbital and CO2 forcing of Late Paleozoic continental ice sheets[J]. Geophysical Research Letters,2007,34(19):L19708.

[4] MONTAÑEZ I P,MCELWAIN J C,POULSEN C J,et al. Climate,pCO2 and terrestrial carbon cycle linkages during late Palaeozoic glacial–interglacial cycles[J]. Nature Geoscience,2016,9:824−828. DOI: 10.1038/ngeo2822

[5] MONTAÑEZ I P,TABOR N J,NIEMEIER D,et al. CO2-forced climate and vegetation instability during Late Paleozoic deglaciation[J]. Science,2007,315(5808):87−91. DOI: 10.1126/science.1134207

[6] ROCHA-CAMPOS A C,DOS SANTOS P R,CANUTO J R. Late Paleozoic glacial deposits of Brazil:Paraná basin[M]//Special paper 441:Resolving the Late Paleozoic ice age in time and space. Boulder,Colorado:Geological Society of America,2008:97–114.

[7] SCHEFFLER K,HOERNES S,SCHWARK L. Global changes during carboniferous Permian glaciation of Gondwana:Linking polar and equatorial climate evolution by geochemical proxies[J]. Geology,2003,31(7):605−608. DOI: 10.1130/0091-7613(2003)031<0605:GCDCGO>2.0.CO;2

[8] SOREGHAN G S,SOREGHAN M J,HEAVENS N G. Explosive volcanism as a key driver of the Late Paleozoic ice age[J]. Geology,2019,47(7):600−604. DOI: 10.1130/G46349.1

[9] MCKENZIE N R,HORTON B K,LOOMIS S E,et al. Continental arc volcanism as the principal driver of icehouse-greenhouse variability[J]. Science,2016,352(6284):444−447. DOI: 10.1126/science.aad5787

[10] GODDÉRIS Y,DONNADIEU Y,CARRETIER S,et al. Onset and ending of the late Palaeozoic ice age triggered by tectonically paced rock weathering[J]. Nature Geoscience,2017,10:382−386. DOI: 10.1038/ngeo2931

[11] KUMP L R,BRANTLEY S L,ARTHUR M A. Chemical weathering,atmospheric CO2,and climate[J]. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences,2000,28:611−667. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.earth.28.1.611

[12] MAHER K,CHAMBERLAIN C P. Hydrologic regulation of chemical weathering and the geologic carbon cycle[J]. Science,2014,343(6178):1502−1504. DOI: 10.1126/science.1250770

[13] 朱先芳,李祥玉,栾玲. 化学风化研究的进展[J]. 首都师范大学学报(自然科学版),2010,31(3):40−46. ZHU Xianfang,LI Xiangyu,LUAN Ling. Progress in research on chemical weathering[J]. Journal of Capital Normal University (Natural Science Edition),2010,31(3):40−46.

[14] BLAKEY R. Mollewide plate tectonic maps,Colorado plateau geosystems[OL]. World Wide Web address,2011.

[15] DONG Yunpeng,SANTOSH M. Tectonic architecture and multiple orogeny of the Qinling Orogenic Belt,Central China[J]. Gondwana Research,2016,29(1):1−40. DOI: 10.1016/j.gr.2015.06.009

[16] 尚冠雄. 华北地台晚古生代煤地质学研究[M]. 山西:山西科学技术出版社,1997. [17] ZHANG Shuanhong,ZHAO Yue,DAVIS G A,et al. Temporal and spatial variations of Mesozoic magmatism and deformation in the North China Craton:Implications for lithospheric thinning and decratonization[J]. Earth-Science Reviews,2014,131:49−87. DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.12.004

[18] LU Jing,WANG Ye,YANG Minfang,et al. Records of volcanism and organic carbon isotopic composition (δ13Corg) linked to changes in atmospheric pCO2 and climate during the Pennsylvanian icehouse interval[J]. Chemical Geology,2021,570:120168. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2021.120168

[19] WANG Jun. Late Paleozoic macrofloral assemblages from Weibei Coalfield,with reference to vegetational change through the Late Paleozoic Ice-age in the North China Block[J]. International Journal of Coal Geology,2010,83(2/3):292−317.

[20] FIELDING C R,FRANK T D,BIRGENHEIER L P. A revised,late Palaeozoic glacial time-space framework for eastern Australia,and comparisons with other regions and events[J]. Earth Science Reviews,2023,236:104263. DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.104263

[21] VISSER J,NIEKERK B V,MERWE S W V D. Sediment transport of the late Palaeozoic glacial Dwyka Group in the southwestern Karoo Basin[J]. South African Journal of Geology,1997,100:223−236.

[22] 路洪海,张重阳. 秦皇岛地区典型地表喀斯特地貌成因分析[J]. 聊城大学学报(自然科学版),2007,20(1):61−63. LU Honghai,ZHANG Chongyang. The formation of typical bare Karst in Qinghuangdao[J]. Journal of Liaocheng University (Natural Science Edition),2007,20(1):61−63.

[23] BERNER R A. Paleozoic atmospheric CO2:Importance of solar radiation and plant evolution[J]. Science,1993,261(5117):68−70. DOI: 10.1126/science.261.5117.68

[24] 邵龙义,董大啸,李明培,等. 华北石炭—二叠纪层序−古地理及聚煤规律[J]. 煤炭学报,2014,39(8):1725−1734. SHAO Longyi,DONG Daxiao,LI Mingpei,et al. Sequence-paleogeography and coal accumulation of the Carboniferous Permian in the North China Basin[J]. Journal of China Coal Society,2014,39(8):1725−1734.

[25] NESBITT H W,YOUNG G M. Early Proterozoic climates and plate motions inferred from major element chemistry of lutites[J]. Nature,1982,299:715−717. DOI: 10.1038/299715a0

[26] FEDO C M,NESBITT H W,YOUNG G M. Unraveling the effects of potassium metasomatism in sedimentary rocks and paleosols,with implications for paleoweathering conditions and provenance[J]. Geology,1995,23(10):921. DOI: 10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0921:UTEOPM>2.3.CO;2

[27] NESBITT H W,YOUNG G M,MCLENNAN S M,et al. Effects of chemical weathering and sorting on the petrogenesis of siliciclastic sediments,with implications for provenance studies[J]. Journal of Geology,1996,104(5):525−542. DOI: 10.1086/629850

[28] HARNOIS L. The CIW index:A new chemical index of weathering[J]. Sedimentary Geology,1988,55(3/4):319−322.

[29] MCLENNAN S M. Weathering and global denudation[J]. The Journal of Geology,1993,101(2):295−303. DOI: 10.1086/648222

[30] 徐小涛,邵龙义. 利用泥质岩化学蚀变指数分析物源区风化程度时的限制因素[J]. 古地理学报,2018,20(3):515−522. XU Xiaotao,SHAO Longyi. Limiting factors in utilization of chemical index of alteration of mudstones to quantify the degree of weathering in provenance[J]. Journal of Palaeogeography (Chinese Edition),2018,20(3):515−522.

[31] PANAHI A,YOUNG G M,RAINBIRD R H. Behavior of major and trace elements (including REE) during Paleoproterozoic pedogenesis and diagenetic alteration of an Archean granite near Ville Marie,Québec,Canada[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta,2000,64(13):2199−2220. DOI: 10.1016/S0016-7037(99)00420-2

[32] 李雅楠. 华北板块石炭—二叠纪冰室期—温室期古环境记录[D]. 北京:中国矿业大学(北京),2021. LI Yanan. Icehouse to greenhouse paleoenvironmental records of Carboniferous-Permian strata in North China[D]. Beijing:China University of Mining & Technology,Beijing,2021.

[33] YANG Jianghai,CAWOOD P A,DU Yuansheng,et al. Early Wuchiapingian cooling linked to Emelshan basaltio weathering?[J]. Earth Planetary Science Letters,2018,492(2):102−111.

[34] BHATIA M R,TAYLOR S R. Trace-element geochemistry and sedimentary provinces:A study from the Tasman geosyncline,Australia[J]. Chemical Geology,1981,33(1/2/3/4):115−125.

[35] RIEBE C S,KIRCHNER J W,GRANGER D E,et al. Strong tectonic and weak climatic control of long-term chemical weathering rates[J]. Geology,2001,29(6):511−514. DOI: 10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0511:STAWCC>2.0.CO;2

[36] YANG Jianghai,CAWOOD P A,MONTAÑEZ I P,et al. Enhanced continental weathering and large igneous province induced climate warming at the Permo-Carboniferous transition[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters,2020,534:116074. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpgl.2020.116074

[37] GRIFFIS N P,MONTA\-NEZ I P,MUNDIL R,et al. Coupled stratigraphic and U-Pb zircon age constraints on the Late Paleozoic icehouse-to-greenhouse turnover in south-central Gondwana[J]. Geology,2019,47(12):1146−1150. DOI: 10.1130/G46740.1

[38] 张英利,陈雷,王坤明,等. 豫西巩义地区上石炭统本溪组泥岩地球化学和富锂特征及其控制因素[J]. 地球科学与环境学报,2023,45(2):208−226. ZHANG Yingli,CHEN Lei,WANG Kunming,et al. Geochemistry and Li-rich characteristics of mudstones from Upper Carboniferous Benxi formation in Gongyi area,the western Henan,China and their controlling factors[J]. Journal of Earth Sciences and Environment,2023,45(2):208−226.

[39] 付亚飞,邵龙义,张亮,等. 焦作煤田石炭—二叠纪泥质岩地球化学特征及古环境意义[J]. 沉积学报,2018,36(2):415−426. FU Yafei,SHAO Longyi,ZHANG Liang,et al. Geochemical characteristics of mudstones in the Permo-Carboniferous strata of the Jiaozuo Coalfield and their paleoenvironmental significance[J]. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica,2018,36(2):415−426.

[40] MONTAÑEZ I P,POULSEN C J. The Late Paleozoic ice age:An evolving paradigm[J]. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences,2013,41:629−656. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100118

[41] FOSTER G L,ROYER D L,LUNT D J. Future climate forcing potentially without precedent in the last 420 million years[J]. Nature Communications,2017,8:14845. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms14845

[42] RICHEY J D,MONTAÑEZ I P,GODDÉRIS Y,et al. Influence of temporally varying weatherability on CO2-climate coupling and ecosystem change in the Late Paleozoic[J]. Climate of the Past,2020,16(5):1759−1775. DOI: 10.5194/cp-16-1759-2020

[43] LU Jing,ZHOU Kai,YANG Minfang,et al. Records of organic carbon isotopic composition (δ13Corg) and volcanism linked to changes in atmospheric pCO2 and climate during the Late Paleozoic Icehouse[J]. Global and Planetary Change,2021,207:103654. DOI: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2021.103654

[44] ZHANG Peixin,YANG Minfang,LU Jing,et al. Low-latitude climate change linked to high-latitude glaciation during the Late Paleozoic ice age:Evidence from terrigenous detrital kaolinite[J]. Frontiers in Earth Science,2022,10:956861. DOI: 10.3389/feart.2022.956861

[45] WANG Ye,LU Jing,YANG Minfang,et al. Volcanism and wildfire associated with deep-time deglaciation during the Artinskian (early Permian)[J]. Global and Planetary Change,2023,225:104126. DOI: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2023.104126

[46] CLEAL C J,THOMAS B A. Palaeozoic tropical rainforests and their effect on global climates:Is the past the key to the present?[J]. Geobiology,2005,3(1):13−31. DOI: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2005.00043.x

[47] ZHANG Peixin,YANG Minfang,LU Jing,et al. Four volcanically driven climatic perturbations led to enhanced continental weathering during the Late Triassic Carnian Pluvial Episode[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters,2024,626:118517. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpgl.2023.118517

下载:

下载: